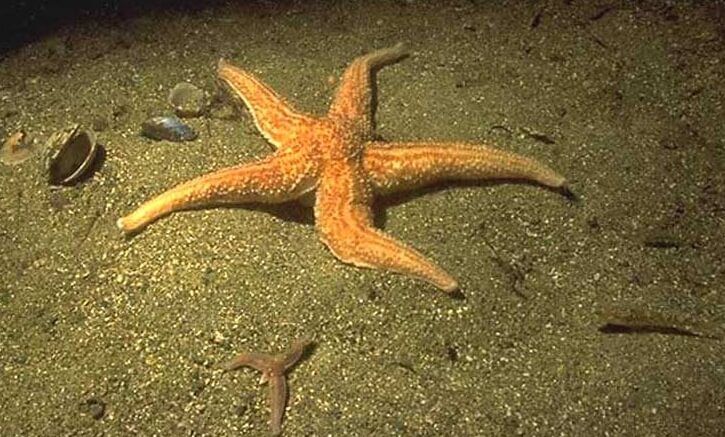

Climate projections for the future of the oceans cast many doubts on the survival of starfish, which are among the most important echinoderms capable of mitigating the ecological effects of other species.

Within just eighty years, our seas and oceans risk losing some of the most famous and beautiful marine species that exist due to the danger posed by global warming.

Scientists from the Marine Ecology Department of the Ocean Center in Kiel, Germany, are convinced of this. In fact, with the article that they published on January 18 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, they showed how the survival of this species could be in danger due to the increasingly frequent and intense heat waves that destabilize the species. In the past decades, these events were very rare and lasted only a few days, but now the average duration of these phenomena has reached a record of about 9 consecutive days, and in the future, it could even be 13 days occurring throughout the year.

This is what most worries researchers, also because the extinction of hundreds of starfish species from our oceans would condemn marine ecosystems to the collapse of the fragile prey-predator relationship, highlighted by the Lokta-Volterra law, which today guarantees the survival of many organisms that cohabit in the same community.

The scientists experimentally tested their model against the Asterias Rubens species, which is the most common starfish in the Atlantic Ocean as well as the Baltic Sea, and calculated the impact of summer heat waves on the consumption of farmed mussels. They grouped 60 starfish into five experiments of 12 individuals each to study five different thermal conditions.

The result was quite disheartening. In experiments with thermal conditions comparable to the future predicted heatwaves (+8°C above average air temperature for 13 consecutive days), heatstroke killed 100% of starfish. This has obviously resulted in an increase in the number of parasites and mussel predators, which have been negatively impacted by the disappearance of starfish. Despite the fact that starfish often feed on mussels, their presence mitigates the presence of more voracious predators and parasites, which could also cause serious damage to mussel culture.

It must also be said that previous exposure to a current heat wave, which has 5°C above the average for up to 9 days, “relieved” the stress of the subsequent ascent, showing that starfish can have a significant tolerance against significant increases in temperature. So all would not be lost. Limiting greenhouse gas emissions could help reduce the duration and intensity of heat waves and save the future of starfish and the ecosystems in which they play an important role.

“However,” say the German scientists, explaining the importance of keeping the duration of these phenomena under control, “the impacts of today’s heatwaves on A. Rubens were only transient, and the starfish could resume feeding after the end of the heat waves. Individuals who have experienced heat waves of today’s intensity and duration have, in fact, consumed as many mussels collectively as starfish who have never experienced a heat wave. In contrast, a pronounced heat-induced reduction in feeding activity during extreme heat events caused an overall reduction in mussel consumption by 53% compared to starfish in the non-heat wave treatment.

Logically, the scientists used a choice of temperatures relative to the forecasts of temperature rise in the coming decades. Therefore, the forecasts obtained can only amaze all marine biology enthusiasts, including experts and mussel producers, who are also affected by the excessive rise in temperatures.

“Our work demonstrates that short-term but extreme impulse events can have a significant impact on marine species,” the scientists conclude in their paper.

“Consequently, heat waves and upwelling will temporarily reduce the in situ feeding pressure of this key predator, A. Rubens, on mussel beds with possible cascading consequences on the entire ecosystem in the western Baltic Sea and potentially other regions of the temperate North Atlantic. However, we are only beginning to understand such phenomena in the marine realm.”

Overall, this study demonstrates the importance of considering environmental fluctuations from now on and the need to evaluate the concomitant effect of extreme events to provide increasingly realistic and accurate projections to politicians and local administrators. In fact, these projections must show how marine ecosystems can transform during climate change, with potentially negative impacts on the survival of species and human beings themselves.”